Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions delivered to your inbox.

Governance, Hygiene, and Growth

When it comes to running a business, we’ve found that there are three core areas operators can focus on: (1) Governance; (2) Hygiene; and (3) Growth. Further, it's possible to view these areas as legs of stool, which is to say that if a business focuses on one more than another, it’s going to topple over. What’s interesting, however, is that rarely do we find a business that pursues all three in balance. But before I get to why that is, let’s define terms:

Governance is the setting up and maintaining of systems that reliably generate accurate information that tells you how your business is doing. (Example: If you operate a business but don’t bother looking at your financial statements because they’re not helpful, you don’t have good governance.)

Hygiene is the deliberate ongoing improvement of best practices in key areas that leads to steady-state improvement. (Example: If your cash consistently lags earnings because you’re not on top of AR collection, you don’t have good hygiene.)

Growth is the generation, prioritization, and execution of new and compelling strategies that leads to a step change in trajectory. (Example: If you haven’t hired and/or promoted 10% of your organization in the past year, you don’t have good growth.)

As for why it’s hard to do all three at once, growth is fun while governance and hygiene are not. Business operators of the more aggressive and visionary kind know this and will pursue growth without regard for governance and hygiene. The problem there is that if you grow without good governance and hygiene, that growth will break your business.

Governance and hygiene, on the other hand, aren’t fun, and what’s worse is that they can be incredibly time consuming. More risk averse operators will focus on these areas and end up not growing either because they don't have the time to think about how or because they consistently see inadequacies in the business that make it uncomfortable to pursue growth. For those folks it’s important to understand that business hygiene can be a black hole in terms of inputs and outputs, so know the difference here between perfect and good enough.

I’ve talked in the past in this space about the four important roles. These are the people who (1) create opportunity; (2) decide which opportunities to pursue; (3) execute opportunities; and (4) measure results. You can also bucket these functions with regards to governance, hygiene, and growth. (1) and (2) drive growth while (2) and (3) watch hygiene and (3) and (4) keep good governance.

Yet for it all to work, the functions need to respect one another and maintain balance. As for how to do that, again, it’s rare, but being aware of the forces at play is step one.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Peoples is Peoples

There’s a rumor going around town that the reason there is one really strict school bus driver who keeps giving out “bus tickets” that prohibit poorly behaved students from riding the bus is because he’s trying to make it so he has the fewest number of passengers so he can finish his route faster and get home while getting paid the same amount. If true, this is a slightly different flavor of quiet quitting, and it’s as insidious as it is brilliant.

Further, this guy must be in cahoots with the delivery person who keeps dropping packages vaguely near the end of our driveway rather than take the five minutes to go up to the house because that’s a job that’s paid to finish routes on time as well. As business philosopher Charlie Munger says, “Show me the incentive, and I will show you the outcome.”

While perhaps we can argue that the school district should propose a more market-based approach where bus drivers are paid based on the number of students they pick up and drop off rather than by the day, the fact is that the labor market is tight. I think many have experienced the reality that businesses and organizations today are hanging onto people despite performance just to keep the lights on.

The stress from worker shortages had previously been considered a temporary phenomenon attributed to knock-on effects from our collective response to Covid-19. Yet The Wall Street Journal argued recently that the crisis is, in fact, a long-term one and that it’s not going to get better. I didn’t know this, but the labor force participation rate peaked in 2000 and has been declining ever since.

What will we do in a world with fewer workers? I think we’re seeing it today: Pay more for lower performance.

There’s another line of thinking that says technology will solve this problem for us, with gains in efficiency more than offsetting losses in manpower. I actually think that technology stands to make the problem worse. After all, technology creates problems that people have to solve. It’s now frictionless, for example, for a customer to register a complaint with a business, and your boss can find you with a gripe at any hour on any day. And I don’t know what your experience has been, but people are far superior at solving my problems than software (No, AI Chatbot, your answer is not satisfactory).

Where does that leave us? We need people, and we need to invest to build them up.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Use Words Wisely

If you don't follow English football, then you may not have heard about the massive refereeing error that cost Liverpool a goal against rival Tottenham. The short version is that Liverpool scored but a player was judged offside by the referee on the field. The call went to video review and that official saw that the player was clearly onside and that the goal should count. So he said, “That’s fine. Perfect,” meaning the goal was fine and perfect.

But!

The referee on the field thought the video reviewer meant the original offside decision was fine and perfect. So he didn’t give Liverpool the goal and restarted play in a match Liverpool ultimately lost 2-1. And when the video reviewer realized what had happened, he said a bad word.

That makes sense in a league where goals are rare and winning and qualifying for the Champions League is worth tens of millions of dollars. In other words, this is consequential stuff, and real damage was done here by someone not taking the time to be helpful and precise with their words.

This is something we are working on with my daughter’s soccer team as well. That’s because while we were practicing, I noticed players with the ball getting confused by all of her teammates yelling “Here!” when they thought they should get the ball.

Because where exactly was “here?” And what kind of pass should the player with the ball make? This would also be useful information!

So we stopped and talked about using words that might be more helpful and precise. Instead of saying “Here” (which gives no information), one could say “Drop” or “Switch” or “Far post” (which does). And that incremental improvement in communication enables the player with the ball and the player calling for the ball to exponentially better collaborate.

Serendipitously, I was rolling all of these thoughts about effective communication over in my head when I lucked into the opportunity to spend a couple of hours talking with 5 Voices co-creator Steve Cockram. He and his co-author Jeremie have a new book coming out about communication codes and how to use them to have more productive conversations personally and professionally. The preview is that there are five material ways to communicate: critique, collaborate, clarify, care, and celebrate, and that you should have a shared understanding about which you’re doing with the person you’re communicating with in order to have the most productive conversation.

For the girls on the soccer team, it’s using words to collaborate with their teammates in order to play the best possible ball. For the referees who botched the Liverpool goal, it should have been clarifying what they saw and then what they heard before confirming the next course of action.

Because at the end of the day, words matter, and Steve and Jeremie’s frameworks are an interesting way to think about them and also use them wisely to maximize their value.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Would You Buy Stock In Yourself?

One interesting way to think about the value of anything is to ask if you would buy stock in it. For example, would you buy stock in Unqualified Opinions? What about Permanent Equity? Capital Camp? Columbia, Missouri?

Me? I’d buy stock in all four of those things, which is why I live where I live and spend my time doing what I’m doing.

I’m also long Sporting Columbia 2012G Navy, The Interrupters, and mushroom hunting, but that’s fodder for another day.

Now I know an easy objection here is “What’s the price?” And that’s fair. Price matters to the success of a transaction. But for the sake of argument here, let’s just assume fair terms.

The reason I think this is an interesting framework is because it forces you to consider whether or not you would give something capital. That’s powerful because providing capital to a person, place, or enterprise is one of the most meaningful things you can do. Not only does it fund that entity, but it shows that you have confidence in it, that you trust it and expect it to increase in value over time, and that you want to spend your time learning more about it or being helpful to it.

It’s been a weird, dystopian idea for a while now but every now and again someone will set up an exchange where people can sell stock in themselves. This is uncomfortable for a lot of reasons, but I think it keeps popping up because the kernel of it is interesting and comes from a place of positivity.

But no, I’m not proposing it.

Instead, I’d suggest making a list of all of the things you spend time on and the people you spend time with and ask and answer the question, “Would you buy the stock?” And, of course most importantly, “Would you buy stock in yourself?”

Have a great weekend.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Competitive Hugs

If you follow him on X, then you probably know that our CEO Brent has been on a bit of a health kick this year. And while I absolutely will continue to make the joke that cholesterol is the biggest existential risk facing Permanent Equity, it’s a pretty impressive feat that he’s gotten close to running a sub-seven-minute mile. What’s more, that is going to make Permanent Equity’s annual Run to Rocheport “fun run” (happening tomorrow!) a bit more interesting.

But you know who else has gotten close to running a sub-seven-minute mile? My 13-year-old son! This has me worried because I have never lost a Turkey Trot in the Family Division, holding off decades of challenges from siblings, cousins, nephews, uncles-in-law, etc. Is this the year that record falls?

I’ll tell you what: I’ve been working my butt off to make sure it isn’t. With both Brent and my son shedding time, I’ve reintroduced more painful speed and interval workouts into my routine to make sure I am still able to run a mile closer to six than seven.

This is the healthy side of competition. It’s a force that can help us all get better at something together.

Yet being competitive is also a trait I have struggled with during my career at the office. In what areas should I compete? How competitive should I be? And in what areas has being competitive helped my career vis a vis areas where being so has hurt it?

After more than 15 years of working with our COO Mark, I think it’s safe to say that he is less competitive than I am. But he’s just as successful, if not more so. How does that work?

It’s with that as background that I had to tweak him when he posted the following cartoon:

“Why do you hate winning?” I responded.

In truth, Mark doesn’t hate winning, and that’s actually what makes us reasonable coworkers. We approach the world with different mentalities, which makes for what Mark calls a “productive dichotomy.”

In order for a dichotomy to be productive, however, you need to respect that the differences you have with a colleague are both valid and interesting. Further, if you’re competitive, like I am, it’s also becoming self-aware that a competitive streak does not give you license to be an asshole.

Candidly, 20 years ago, given the same set of circumstances if either Brent or Ben ran me down in a race, I’d have been pissed. If it happens this year or next, I’m going to give them a hug.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Tell People You’re Different

I am doing you a solid here by letting you know that if you ever get the invitation to travel with our COO Mark, you should politely decline. The reason is he’s cursed. His flights are always delayed, impacted by weather, landing at the wrong airport, etc.

The silver lining of this is that it gives him a lot of time to unleash lengthy threads on Twitter (or whatever that Musk guy is calling his platform now). So it went the other day when he had another long layover and invited people to ask him anything because I guess he was bored.

One interesting question he received was from Ben Tiggelaar who wanted to know “What’s the Permanent [Equity] strategy around all this focus on social? So interesting given no [private equity] firms really focus on content.”

It was a good question and an astute observation, but the answer is a simple one: Because it makes sense.

As Mark replied, we know it adds value because both he and I first encountered Permanent Equity on Twitter and also because our funds originated as a result of a relationship Brent first built on the platform.

And as I added, we know that online content scales conversations and find that it’s an advantage for people to know us and what we’re going to say before they actually know us or we say anything. That’s because our value proposition and approach to investing are consistent, and we try to always do what we say we are going to do. At the risk of making a straw man argument, I suspect other private equity firms don’t publish content about what they do because either (1) they don’t want people to know or (2) they want the latitude to say whatever it takes to get a deal done.

Something that’s interesting is that if you have a problem, there are usually lots of solutions that will work once, but it’s harder to find a solution that will work sustainably. With regards to making investments, attracting investors, and recruiting, by laying a long trail of content that describes what we do and how we do it, we believe that things in those categories that would be a good fit for us will eventually find us. And also that that approach is superior to doing what it takes to capitalize on available opportunities. That means going long stretches without doing anything sometimes, but also never doing anything we don’t know or want to do.

So in short, be different and genuine because you can always be that, and if you are, tell people about it. But also, never travel with Mark.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Beer Money

Back during Season One we occasionally published a piece called CIMple Truths, which was a compilation of ridiculous claims and presentations we’d seen recently in deal teasers. I retired the template for Season Two because (1) the gag didn’t resonate like I thought it would and (2) we haven’t been seeing as much ridiculous stuff. (1) is on you guys because I thought they were hilarious, but (2), I think, is a product of higher interest rates and a more subdued dealmaking environment keeping weird stuff away from the market (Trump and Chamath and all of the other weirdos would never launch SPACs now).

But!

I am unretiring the format today because I have never seen anything as ridiculous as this:

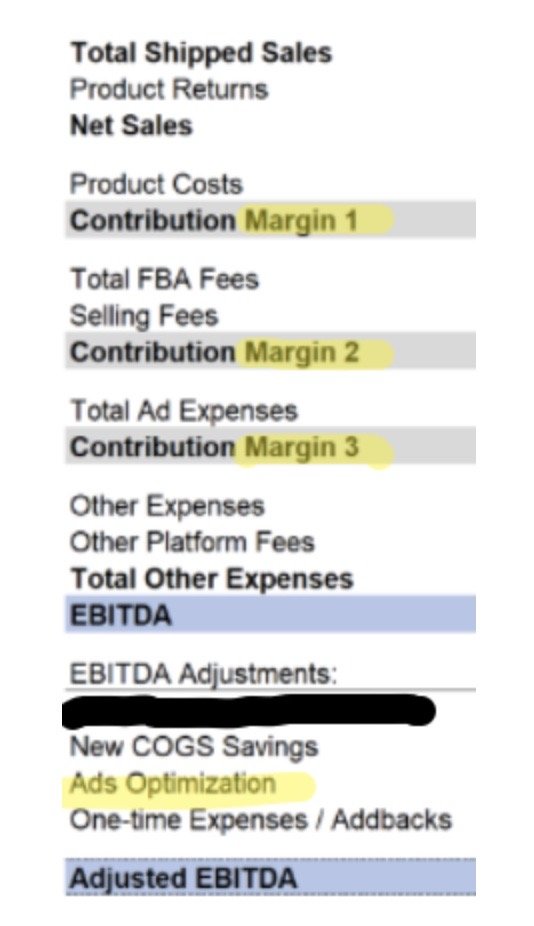

I left out the numbers because they don’t even really matter, but what is the thought process behind presenting three different kinds of “contribution margin”? Because a business’ level of profitability before accounting for marketing and distribution costs is not only not a thing, it’s irrelevant!

The reason that’s so is because without marketing and fulfillment, there is no business.

I’m dating myself here, but I am old enough to remember Groupon and ACSOI. ACSOI was a measure of that company’s profitability if you didn’t include what it cost to acquire customers or what it paid employees in stock-based compensation. Again, no customers or employees, no business! There is no world where you should add back or adjust out critical functions. And don’t get me started on adding back hypothetical earnings from counterfactual “optimizations.”

This is why we measure the value of a business in terms of how much beer money it produces. You could also call this really free cash flow. This is the money, all of the accounting shenanigans and GAAP yada yadas aside, that you have leftover at the end of the day that you can withdraw from a bank account to buy beer with. And, if you have a lot of it, cheers.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

An Unavoidable Opinion

I’ll come clean: when the FTX and Alameda complaint against SBF’s parents was released, I hoped it would provide fodder for the rest of Season 2 of Unqualified Opinions. Unfortunately, nothing in that complaint was funny or clever or even interesting. Instead, it was gross, with the epitome of grossness being SBF’s dad complaining in an email to his son that he wasn’t being paid enough to do nothing and cc’ing SBF’s mom to solve the problem. Yuck.

So that meant I also wasn’t that interested in reading Michael Lewis’ new book Going Infinite about the whole sordid and illegal (and gross) affair. That is until Matt Levine of Money Stuff started excerpting from it and then the trial started and then it was everywhere, and so I was unavoidably pulled back in.

Now, as chair of Permanent Equity’s Matt Levine fan club, you can rest assured that I don’t find fault with most of what’s published in Money Stuff, but this whole SBF/FTX saga has been so bizarre (and gross) that it’s prompted people to take some unexpected positions. For example, here was Levine opining on SBF’s first employer, investment firm Jane Street, and its practice of requiring interns to learn how to bet against one another:

It is optimal for a firm like Jane Street with a lot of traders to encourage each of them to take a lot of positive-expected value risk, because Jane Street has enough of them to benefit from the law of large numbers. With enough independent positive-expected-value bets, it will make money, even if some traders lose money.

And then here he was carrying that line of thinking through to a discussion of public company CEO compensation:

This is analogous to why corporate chief executive officers are often paid with stock options: It encourages them to take the amount of risk that is appropriate for their shareholders. A CEO generally has a huge chunk of her human and financial capital wrapped up in her job, and it is very important to her not to lose it. So she will naturally be conservative, preferring steady mediocrity to risky expected value maximization. But her shareholders are diversified funds who own lots of companies and want each one to maximize expected value. So they adjust her utility function by giving her stock options that pay a ton in the upside cash and nothing in the mediocrity case.

Say what?

In the case of Jane Street, yes, that math can work for some period of time, maybe even a lifetime, but the reasoning falls victim to the fallacy that a lot of independently stupid decisions can sum to a broader good decision (they can’t!). Further, it underestimates the likelihood that if one bad thing happens, it will make it more likely for other bad things to happen. For example, if the market got wind that some Jane Street traders were getting smoked, it would likely start actively trading against the other Jane Street traders.

In the case of executive compensation, the CEO in this strawman, who is probably already financially secure, has every incentive to be reckless in order to get those options to pay off because she stands to gain a lot and lose very little. This is why so many public companies lever up to repurchase shares. Doing so risks up the business, with that risk being borne by shareholders, in order to jumpstart the stock price, with that reward being reaped by the options-holding CEO.

Yet Levine isn’t the only one that SBF/FTX has gotten to think funny. The aforementioned and previously unassailable author Michael Lewis (Moneyball remains a classic) seems to have fallen victim to a con, writing 288 pages about a visionary who was actually just a criminal and not bothering to verify any number of wild claims. Moreover, he seems to be doubling down in recent interviews that SBF, despite an objectively incriminating fact pattern, is simply some kind of misunderstood. Asked point blank if he believed SBF was a serial liar, Lewis responded, “I think he’s a serial withholder. Unless I asked exactly the right question, I did not get the full picture.”

Which, you know, is what happens when someone is a liar.

Anyhow, there is still more trial to come, and everyone is assumed innocent until proven guilty, but my opinion, in case you missed it, is that it’s gross.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

They Blew Up the Bridge

Not long ago they blew up the Rocheport Bridge, which was how Interstate 70 crossed the Missouri River near Columbia. We live near there and have river access and friends with a boat (which is way better than owning a boat in terms of risk/reward profile), so we went down that morning to get a good view of the explosion. Not only did we get that, but we also got video, and I have been racking my brain ever since about ways to connect that video to some kind of business, finance, or investing lesson so I could share it in this forum because it’s pretty freaking cool.

Nothing worked, though, so I finally decided, “Screw it. Sometimes it’s fun just to watch stuff blow up.” So here you go and if you’re able to find a business, finance, or investing lesson in here somewhere, (1) all the better; and (2) let me know what it is.

Have a great weekend.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

What’s Partnership Worth?

We had an exchange the other day with some folks who were trying to decide between selling some of their business to us or doing nothing and just keeping it (which is our biggest competitor). To help them make that decision, a spreadsheet got built that looked at how the business might perform in the future and then compared the cash flows that the sellers might receive were they to sell some now and own less later versus sell none now and take all of the distributions later.

It should go without saying that if the sellers kept 100% of the business, they would receive more money over time than if they sold. The reason for that is that any buyer requires a return on their money and that return is what you as the seller are foregoing in order to put the buyer’s money in your pocket today. But a today dollar is worth more than a future dollar and particularly so if the prospects of earning that future dollar are uncertain, so you need to discount those unpredictable future dollars to make an apples to apples comparison.

This is all vanilla present value/future value stuff, but where it gets interesting is when you start to think about how much of a discount those future dollars deserve. The reason this topic arose is because we modified the spreadsheet to show that we believe that it was worth about the same in total present value for the sellers to sell some to us rather than keep it all themselves.

To which they reasonably replied, “Well, sure, but you are using a lower discount rate on the scenario where we sell and a higher discount rate where we don’t. If you use the same discount rate, not selling is worth more.”

To which we reasonably replied, “Well, yes, we are using different discount rates, and while we could debate what the discount rates should be, we feel strongly that they should at least be different.”

And the reason they should be different boils down to the value of partnership. If you’re running a business on your own, without access to outside capital, and with no team of experienced professionals standing by to be helpful, are you less, equally, or more likely to achieve growth and success than if you do?

If your answer is less or equally, think hard about why you’re bringing on a partner. Because if you’re bringing on a partner, the answer should be an emphatic “Yes, the business is more likely to achieve growth and success with this partner than without it.”

And so your discount rates are different…

And so partnership is worth more…

As for how much more, well, that’s why this stuff is more art than science. But don’t just take my word for it. I’ll give the last word here to our friend and business owner Mike Botkin, who said this about a good partnership:

“Having a partner…is a cheat code. It’s a true 1+1=100. From nitty-gritty, to brainstorming, to strategic decisions, to just BS-ing on the phone…Having a partner in business, like life, is crucial and critical.”

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Relevant, Useful & Beautiful

Our resident curmudgeon and chief legal officer Taylor Hall recently passed along this article that reported that “the vast majority of NFTs are now worthless” with the commentary “Did NOT see that coming.” Of course, I can’t let Taylor take a victory lap here without also bringing up the fact that at one point he was knee-deep in NBA Top Shot.

“Knee-deep,” though, is not as deep into NFTs as a lady we met in New York was, who made the case that because NFTs were the only things in the world that were truly non-fungible and unique that their value was inherent and that everything in the future would be “on chain.” I hope she didn’t quit her day job.

The stats, though, are nuts:

95% of NFTs are worth zero.

23 million people hold worthless NFTs.

79% of NFTs never even got sold due to the massive supply/demand imbalance.

The report concludes “In order to…have lasting value, NFTs need to be either historically relevant, true art or provide genuine utility.”

The point here is not to dunk on NFTs or the people who bought them, though it’s obvious in hindsight that all of the signs of a bubble (suspension of disbelief, rising prices, FOMO, inexperienced market participants, etc.) were there. Rather, it’s to point out that that framework is a pretty good way to think about the value of anything. For something to be truly valuable, it has to be relevant, useful, or beautiful, and ideally more than one or all three.

Your house? Relevant because it gives you somewhere to call home. Useful because it keeps you safe and warm. And I hope you find it beautiful. Clearly valuable.

Money? Relevant to all of your transactions with others and useful because it buys the things you need. And there’s a reason numismatics is a thing. People have taken time to make something as valuable as money beautiful too.

Stocks, you might argue, are none of those things, but stocks are derivatives of beauty, utility, and relevance. A share of Apple, for example, represents that an iPhone is all three of those things to its users.

This is all to say that NFTs aren’t inherently valuable or not. Nothing manmade is, unless it’s well-made, thoughtfully, and with a purpose.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

You’re Winning? Stop Watching.

Danny and I were chatting recently about Mizzou’s subdued (until they defeated Kansas State on a thrilling last second 61-yard field goal and started rolling, last weekend excepted) start to their football season when he admitted that he stopped watching at halftime of their narrow week 2 victory over Middle Tennessee State. The reason, he reasoned, was that if he kept watching, the best case was that they eke out a win and the worst was that they blow it, neither of which seemed like entertaining options, so there were better ways to spend his time.

I admitted to doing the same mental gymnastics when the Georgetown Hoyas basketball team would go into halftime with a big lead (though that hasn’t happened in a while). With the range of outcomes being a benign second half to a disastrous collapse, there really wasn’t any reason to watch further (unless you’re a masochist).

This is what happens when one views the world in terms of upside and downside.

A good book about investing is The Dhando Investor by money manager Mohnish Pabrai, which is mostly remembered for its observation that you want to buy into situations where your risk and reward are asymmetric. Or as Pabrai puts it, “Heads I win; tails I don’t lose much.”

Of course, the issue with that is that you can always lose everything, as Pabrai himself found out years after The Dhando Investor was published with his investment in Horsehead Holdings, a metals business that seemed cheap by any measure but ultimately declared bankruptcy. Explaining the outcomes to partners, Pabrai said:

We ended up with a trifecta of low probability events in unison. They ran into very significant ramp-up difficulties on a proven process. At the same time, zinc prices collapsed to levels not seen since the financial crisis. Nickel prices have collapsed to a multi-decade low. All of these decreased profitability and increased the need for cash at the very same time their liquidity was becoming quite stressed.

The learning is that we underestimate the probability of negative, low probability events happening at the same time. I’ve newly minted this the Hurriquake Principle, which is to say that just because you’re experiencing a hurricane doesn’t mean you can’t also have an earthquake. But when it comes to business, I’d go a step further and assert that experiencing a negative event makes another negative event more likely to occur because stress begets stress.

Now, I know you can’t just turn off a business, but the point is that if you find yourself in a situation where the upside is capped, walk away! That’s because limited downside is an illusion, so you can only be compensated with upside. It’s the same asymmetric orientation as Pabrai’s, but inverted to account for the fact that bad things can always happen – a reality well-known to Mizzou football and Georgetown basketball fans alike.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Hard Skills and Self-Discovery

After she read “Be Ambitious,” Kelie (our Director of Talent Acquisition) responded with an article about “squiggly” careers. This is the idea, named by authors Helen Tupper and Sarah Ellis, that the best career paths are non-linear because they lead to rounder development and greater possibilities. A decade back, then Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg made a similar argument, but used the analogy that you should think of your career path like a jungle gym, where you can climb anywhere, rather than a ladder, where you can only climb the next step up.

Broadly, I agree with this thinking and have tried to live it.

What’s interesting, though, is that all of this opining on the importance of de-regimenting career paths comes at a time when it seems to be the case that college students are more likely to pick majors that would put them on a more regimented career path. For example, here are the five college majors that gained the most market share over the past 20 years:

The major with the most market share remains business, at 18.9%, but that’s down more than 2% from 20 years ago.

As for which majors have lost the most share, aside from business, it’s education (-4.7%), social sciences and history (-3.1%), English (-2.6%), and liberal arts (-1.2%). As an English major who graduated from a liberal arts college, I weep for our future. (You can find the data here.)

Not really; I’m an optimist when it comes to things like economic growth and development. Moreover, and at the risk of generalizing, I don’t think this seeming inversion in trends (humanities majors happy to be on stable career paths versus hard skills majors who pine for self-discovery) means we are as different now from then as we might think (despite all of the shade different generations like to throw at one another).

Rather, I think it’s the case that people want to be both well-rounded and successful. Perhaps in the past, when college was less expensive, there was less pressure to learn a marketable trade because you could find structure in your career. Now that it’s more expensive, I know many feel the pressure to graduate into a career path. Yet just because someone learned to code doesn’t mean that that person isn’t also interested in people and philosophy. Except for the software developers we all know who have no interest in people or philosophy.

Yep, we know who you are.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Hey. Pick Up the Phone.

There’s a big difference between illiquidity and insolvency, but the former can feel pretty stressful when there’s a bill to be paid and nothing but assets that aren’t cash on the balance sheet. “Can I pay you with this inventory I haven’t sold yet?” is not something your suppliers want to hear.

So it was at one of our companies that was cash poor with $1M of bills to pay and several million of AR on the balance sheet. In other words, the money was there, but it wasn’t in cash, so we were on the verge of a crisis. Yet by the end of the week, we’d paid our bills and stacked more than $1M on the balance sheet.

What happened? We picked up the phone.

As it turns out, when we were told that the company had done everything to collect its overdue receivables, “everything” including everything but picking up the phone to call the people who owed us money. We had texted them, emailed them, slacked them, emailed them again, and complained loudly to others in the office that we hadn’t been paid yet. Shocker, none of that worked.

In an era when someone can communicate at length without ever actually having to talk to someone else, I think we’ve lost sight of the power of conversation. My experience is that if you need to persuade, cajole, convince, ask, tell, flatter, or correct, it’s all better done over the phone or in person. And in our line of work, we see the power of a phone call over and over again.

Why has actually talking to people gotten so hard? Heck if I know. But we’re all guilty of it. Just pull up your cell phone and compare the last time you texted someone to the last time you actually talked to them.

Or compare the number of texts you’ve sent to the number of phone calls you’ve made. Sure, you might argue that texts are shorter and more efficient, but sometimes we should value quality over quantity. Think about the value of calling someone and saying “Hey, I was just thinking of you” and hanging up. That’d probably make their day.

I think a new best practice is if someone you haven’t talked to in a long time texts you, instead of texting them back, call them back immediately and have a real conversation. I bet both of you will be glad you did.

Have a great weekend.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Big Pops

If you’ve been watching closely, you may have noticed a change in Permanent Equity’s content strategy. While we’ve always been passionate about sharing thoughts and ideas with the world, there are lots of ways in which to do that and we have tried (and failed but also succeeded) nearly all of them.

If you go back to this time last year, our attempted cadence was generally a podcast or an essay per week that resulted in a semi-regular topically-driven email. While this was fine, the metrics told us that while we were engaging existing audience, we weren’t reaching much, if any, new audience. And, qualitatively, it felt like we were forcing things to fit the calendar, publishing even if we didn’t have anything compelling to say, but also not giving ourselves the time to really dive deep when we did.

So we all got in a room and asked what is a compelling, measurable, and achievable stretch goal for our content? What we came up with is that we wanted to publish content that would get us invited to speak somewhere. The reasoning was that if this happened it probably meant that we had reached new audience, produced something that had compelled someone to reach out to us in a meaningful way, and opened up a new avenue for opportunity.

That was why we made the decision to refocus energy and resources on one very in-depth piece.

But!

We also didn’t want the world to forget about us while we were diving deep.

When it comes to negotiating deals, we love the middle ground, but when it comes to risk management and strategic initiatives, we generally loathe it. That’s the barbell; the idea that there is no medium risk nor medium effort.

The way that manifested itself in our content strategy is that we stopped publishing kinda long podcasts and essays weekly and started doing something daily and punchy (that’s this) complemented by something infrequent and unpredictable, but remarkable (that was “Do Diligence,” the open sourcing of our diligence process that our CEO Brent called the best piece of content we’ve ever produced).

So now we’ve got a steady state with the potential for big pops, and that feels more right.

That has got me thinking about how we might apply this concept to our businesses. In other words, is there something that we could be doing that’s small, frequent, and relatively straightforward that would cover our costs, freeing up resources to do something big, but infrequent, that when it happened would drop straight to the bottom line? Or, if it’s a more volatile business that already trafficks in big pops, is there a service line we could start that would make the time in between pops less stressful?

Because it’s important to go big, but you also never want the world to forget you exist.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Are You Selling or Taking Orders?

We encounter a lot of businesses with salespeople on staff, and when we do, one of the first questions we ask the owner or operator is “Are they salespeople or are they order takers?” That’s because our experience is that many people who think they do sales aren’t actually proactively selling anything. Instead, they are nurturing existing relationships and facilitating transactions when a customer comes to them.

Noting this is not to denigrate that as valuable work. Having good order takers is important. They’re responsible for making sure a business maintains loyal customers and increases average order value over time. But what makes a good order taker is often different from what makes a good salesperson. Or as the head of sales at one of our businesses puts it, there are hunters and there are farmers.

A good salesperson, unlike an order taker, is full-time doing the work of finding new customers. That means searching in new geographies, categories, and industries for novel business. This is important work because outsized growth comes from combining new and organic growth.

Our experience, though, is that making sales is more difficult than taking orders in the sense that the hit rate is lower (repeat customers are much more likely to make a purchase than new prospects). Further, prospects are likely to make smaller initial buys than repeat buyers, which means anyone who works on commission is incentivized to become more and more of an order taker over time, a reality that is detrimental to the long-term health of a business. Further, a salesperson may be unwilling to hand off a customer to an order taker who might be better at nurturing the relationship because it’s in the long tail of that relationship where he or she will make their money.

Here’s an example…

We met with a manufacturer recently who had five US salespeople covering the northwest, southwest, midwest, northeast, and southeast regions. When we asked how they spent their time, we were regaled with stories of how they worked with existing customers to make and fulfill orders. So we asked who was in charge of finding new customers and were told they were and they had acquired 20 new customers in the past year. So we asked how they had acquired the customers. The answer was that all of them had come to visit their booth at a trade show. So we asked if anyone had looked at gaps in the customer base and proactively reached out to potential customers who had not already shown inbound interest. Crickets.

This business had great order takers, but no salespeople. So hire a salesperson, we advised, and give them residual interests in the new customers they acquire for you so he or she will always be scouting for new business while letting the order takers build relationships. Not only should that person clearly pay for themselves over time, but by separating the functions of sales and order taking, it’s easier to delineate who is doing a good job in the numbers. That’s because a salesperson should be measured on new accounts and an order taker on average account size. Because when the two are smashed together and a combination salesperson/order-taker is measured on revenue, a shortfall in one area can be masked by performance in the other, even though a good business needs both.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Build the Box

After I wrote about how we try to stay inside the box, I received a response from Chris who said this:

The concept of the box is not a new one to me, but I am interested in how it is applied at Permanent Equity. Are there any more resources that are already published that you use to create your box? Templates, budgets, or how you think about variance? I'm looking for a little bit more detail on the actual structure and methodology.

I started to respond, but then thought if Chris was interested, others might be too, so why not reply all?

One of our weaknesses/strengths at Permanent Equity is that we don't require uniformity from our portfolio companies, so each one does a slightly different flavor of budgeting/forecasting. Further, they're all pretty different business models, so a standard specific approach wouldn't be well received. That said, each process has common elements and typically breaks down as follows:

Identify top line drivers and how those will manifest as revenue over the time period. For our construction businesses, this is as simple as looking at the backlog. For our consumer businesses, there's a bit more voodoo with regards to marketing spend and conversion rates.

Since we are typically managing to free cash flow and return on invested capital, the next step is to make sure our revenue forecasts support our spending plans with an acceptable margin in between. What's acceptable depends both on the reality of the business model and on agreed upon reinvestment priorities. Typically if we lack visibility into (1), then (2) will be tighter and/or contingent upon performance with spend unlocking over the course of the year as we gain visibility into the top line.

With those variables determined, we load monthly and quarterly projections into a spreadsheet and then track top line performance and FCF against plan, paying particular attention to earnings quality, which we define as the actual percentage of earnings that hits our bank account (ideally 90% or better). While we don't much mind monthly variance, conversations are generally prompted if earnings quality is low (i.e., how can we manage cash better?) or if greater than 20% variance persists for a quarter or more. The reason I set the bogey at 20% is that it's an acknowledgment that we live and work in the real world, that precision is false, and also that the margin profile of our businesses is usually 20% to 40%, so if we are missing or exceeding by 20%, we're probably materially over- or under-investing relative to what reality would dictate we do.

That’s what it means for us to get outside the box – when we do, it causes us to start thinking hard about turning things on or shutting them down in order to course correct. Because ultimately our goals are to earn an acceptable return on our investments and also never be surprised.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

Morgan Housel’s Costco Gaffe

It dawned on me that we are two months into Season 2 of Unqualified Opinions and I haven’t taken any gratuitous shots at my former direct report now best-selling author and global phenomenon Morgan Housel. That stops now.

Fortunately, Morgan provided fodder for a shot recently when he X’d Charlie Munger’s assertion that the reason there are no good interviews with Costco founder Jim Sinegal is that he was “too busy working,” calling Costco the “ultimate no bullshit, pure value-add company.” The reason this is fodder for a shot is because he apparently failed to remember that when we both worked at The Motley Fool, Sinegal gave us multiple interviews. In fact, my favorite Jim Sinegal story is the time Mac, who booked interview guests, called Costco to first ask if Jim would sit down with us expecting to get some administrative assistant only to have his call answered on the other side by someone who barked “This is Jim.”

Yes, Sinegal answered the corporate line himself, which is the ultimate representation of a no bullshit, pure value-add mentality.

Anyway, my shot at Morgan now taken, I’ll say that there are a lot of pieces of wisdom in those interviews with Jim, but I’d like to call out two.

The first is the concept that to be successful in business you have to know who you are and not forget it. Sinegal says that the graveyard of retailers is filled with people who “lost their way relative to what their original concept was.” People shop with Costco, he notes, “because we have great value on great products” and that Costco aims to be demonstrably better on price “on every single product we sell.” And that is why the company doesn’t advertise. Because it would raise operating costs that would have to be passed along.

Stretching for growth, it would have been easy for someone to say, “Hey, why don’t we just start advertising? The customer won’t notice slightly higher prices.” Not only would the customer notice, but that would start the cultural drift that would eventually undermine the business.

The second is the idea that when you start something, you won’t know where it will end up, so don’t lock yourself into anything. “Our original business plan showed that we could eventually grow to 12 Costcos…and we’ve missed the original plan,” said Sinegal. Today there are 859 Costcos in the world, so the plan wasn’t even close. This is why you preserve open-endedness. When something goes, you want to be able to go with it.

And Costco still has room to go. I mean, we still don’t have one in Columbia, Missouri.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

You’re a High Performer, Relax

I particularly enjoyed the last few minutes of Oppenheimer (which was better than Barbie). As I’m not sure if I need to add a “spoiler alert” before talking about a biopic, be forewarned that the following discusses details of the film other than the creation of the atomic bomb that we all knew about before walking into the theater. Let’s press on…

In the last moments of the film, Strauss is complaining that Oppenheimer turned the scientific community against him thereby denying him a cabinet confirmation citing a scene where Oppenheimer met Einstein at a pond in Princeton under Strauss’ watch after which Einstein walked away without giving Strauss a second glance. Hearing these complaints, Strauss’ unnamed confirmation hearing handler, who starts out a sycophantic know-it-all but turns into an antagonist-cum-saboteur after realizing Strauss to be a realist politician (though maybe that’s redundant), says that maybe just maybe Strauss has it all wrong.

They might have, he points out to Strauss, talked about something more important than you.

Then we see in a moment of clarity that Einstein and Oppenheimer, two of the most brilliant scientists to walk the face of this Earth, didn’t use their few minutes together to kvetch about Strauss, but rather to ruminate about the fate of the world in light of each of their discoveries.

Go figure!

Strauss, though, is a high performer. And Strauss really was a high performer, his accomplishments undeniable. But even if your high view of yourself is correct, it doesn’t mean that other people are always talking or thinking about you.

Which may also have been Oppenheimer’s problem…

The point is, if you’re a high performer, people see it; you don’t need to throw it in their faces. And also that one should give others the benefit of the doubt. If you’re excluded from a meeting that you thought you might be a part of, it could be the case that people aren’t freezing you out, but are rather being respectful of your time.

Can you go unseen for a while? Sure. But relax. Maybe I’m wrong, and I will die on this hill if I must and I’ve said it to my own kids and kin so I am eating my own cooking, but the world is more merit-based, and more people want it to be so, despite injustices, than it appears.

Have a great weekend.

– By Tim Hanson

Sign up below to get Unqualified Opinions in your inbox.

This Is Not Pessimistic

As much as I love spreadsheets, I’ll be the first to admit that financial modeling is more art than science. In fact, last season, when I called Excel the cause of and solution to life’s problems, I observed that “one of the most dangerous situations you can find yourself in is one where “the numbers make sense [because] if you’re falling back on the fact that the numbers make sense, then it may be the case that the sense doesn’t make sense.”

I thought of this the other day when I received a financial model from a friend who wanted me to take a look at it. He was thinking about making an investment and asked that I double-check the numbers. Like many financial models, it included scenario analysis. This is to say that there were projections of what would happen numbers-wise if things went less well than expected, as expected, and better than expected. And one of the reasons my friend was confident in the investment is that even if things went less well than expected, he’d modeled that he’d still make money.

Unpacking the assumptions, I noticed that the “pessimistic” models, like many “pessimistic” models, forecasted lower growth rates and margins, which stands to reason. But what didn’t stand to reason is that the poor performance was linear. In other words, in one model, the business grew less than expected, but it still grew every year. In another, the business shrunk, but the business shrunk the same amount every year. And in a third, margins compressed, but it assumed that operating expenses could be cut at the same time.

This is not pessimistic!

The reason is that while all of these models assumed disappointing results, the disappointment was linear. The world, however, is not linear, so any model that assumes linearity is wildly optimistic!

Think about it this way: If I told you that I had a business that grew 2% per year, you probably wouldn’t be that impressed. But a business that is guaranteed to grow 2% per year is really valuable because it offers certainty. You can borrow against that, cut every decision close to the line, and never worry about dealing with downside. Even a business that is guaranteed to shrink 2% per year is valuable at the right price for the same reason. Even though it will eventually go to zero, there is no chance of an outsized downside surprise.

So what I said to my friend was, and this was a commodity business by the way, is that your risk here is not low growth, but volatility. If you put debt on the balance sheet and pricing moves against you for a six-to-12 month period, it’s game over even if this would have been a good long-term investment. What you need to do, if you really want to be pessimistic, is forecast high levels of volatility and figure out if the numbers make sense against that backdrop. That’s because the definition of pessimism is believing that the worst will happen. And the thing about the worst thing that can happen is that it’s not predictable.

– By Tim Hanson